The secret of a company’s success is never based on a single factor. The strategic business elements (business vision and model, strategy and quality of the organization) are always key success factors. However, sometimes the simplest and most operational factors —if not well resolved— are the main obstacles standing between an adequate strategy and its results. The choice of decision-makers is frequently one of these.

The combination of a business vision with a well-designed strategy and the proper organization of a professional, motivated and aligned team is a necessary condition of success for any business. But these important elements, which form the basis of strategic business planning will be insufficient if you do not take action: realize the vision, implement the strategy and achieve optimal team performance.

In a start-up or small business, the step to action is easy and immediate, since it is the founders who design, decide, execute and adjust the plans in the way they think is most appropriate. But as the business grows and the organization becomes more complex, this step from strategy to execution becomes more complicated.

To turn a strategy into results and achieve excellence in execution in a more complex organization, a second level of management tools is needed: for instance, the definition of key business processes (backbone of the value chain), effective resource allocation, organizational design, controlling systems, human resources management, standard procedures (who and how does what) and, not least, a proper decisions allocation. The decisions allocation consists of a clear, consistent and unequivocal definition of who is empowered and accountable for making each type and level of decisions. The attribution to people, functions or teams of the capacity and responsibility to make the decisions that ensure the execution of the plan (who decides what) is clearly set in the decisions allocation chart.

Counting with an adequate decisions allocation chart does not guarantee the efficiency of the decision-making process or the quality of the decisions: a solid definition of the key business processes should take care of that. But not having this management tool, as simple as it is relevant, might potentially jeopardize the company’s success. Surprisingly, this is the case of many companies, with various negative effects analysed below.

ALLOCATION OF DECISIONS: CLARITY IS KEY

All the company’s team members, from the chairman of the board of directors to the most junior factory worker, going through all hierarchical and functional levels, constantly make decisions that impact on the value chain and the business result.

Logically, the number and importance of the decisions assigned to the individuals vary according to their function and their position in the organization. In addition, there are decisions made in groups and, even, there are decisions delegated in an algorithm or computer program.

Paradoxically, the allocation of decisions does not always receive the attention it deserves and is often limited to the financial and legal field: for instance, establishing who can buy or pay or who will receive powers of attorney so that their decisions have effects before third parties.

When business decisions allocation is flawed, incomplete, improvised, inconsistent or simply non-existent, the organization is very likely to fall into what I callthe decision-makers’ trap. This has several potential harmful and persistent effects: on the quality of execution, on the ability to correct and learn from mistakes, on the motivation and quality of the staff and, finally, on the success of the strategy.

A CLEAR ASSIGNMENT OF DECISIONS AND ACCOUNTABILITIES

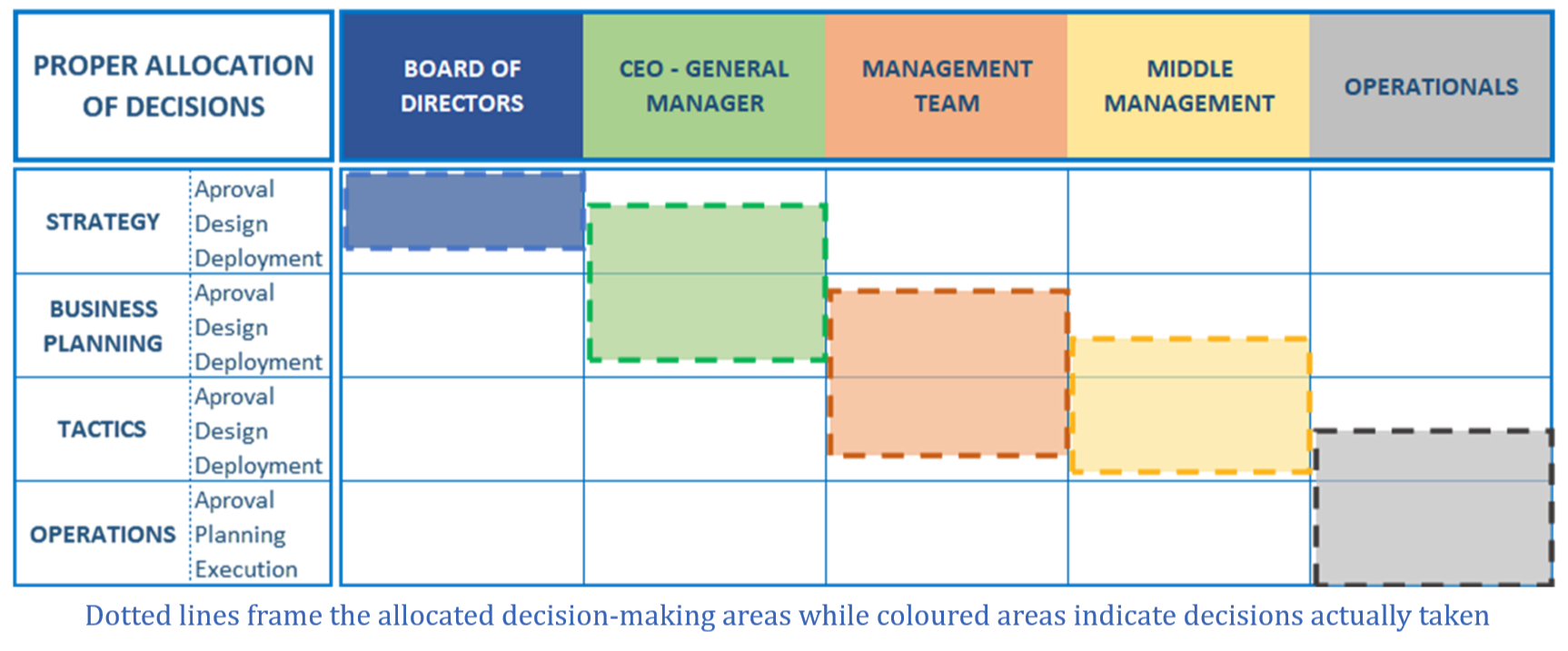

The decisions allocation chart of an organization counting with an adequate decisions assignment might look like this:

Each organizational level is assigned -individually or as a team- a set of responsibilities and decisions, of a strategic nature at board / management level and more operational at lower organizational levels. Every individual knows their attributions and responsibilities, takes autonomously – according to their best professional criteria – the decisions that correspond to them, rectifies or adjusts them when necessary and is accountable for the result.

THE DECISION-MAKERS' TRAP

The problem arises when, for various reasons (rapid organizational growth, lack of trust in the team, weak leadership, difficulties in delegating, insecurity in the face of weak control systems, etc.), the decisions allocation chart becomes blurred or -more frequently- is not respected in practice.

The most common situation in these cases is that, occasionally or systematically, consciously or not, some people invade decision areas assigned to lower levels, making or —even worse— correcting or reversing decisions that should correspond to lower-ranking managers, middle managers or even operating staff.

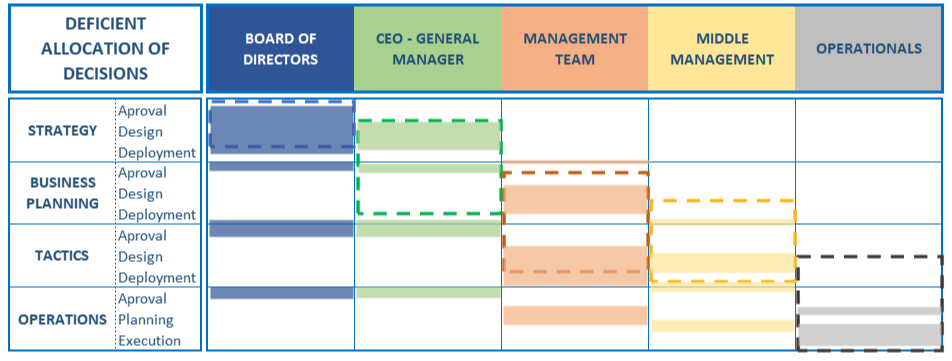

A decisions allocation chart example that would illustrate a generalized case of such a dysfunction could be as follows:

In the example above, higher organizational levels invade the areas of responsibility assigned to their teams. All decision areas are affected and some decisions are not made. This company has fallen into the decision-makers’ trap.

A BEWILDERED ORGANISATION

Although the foregoing is an extreme example, it is helpful to analyse the potential harmful effects of this type of dysfunction:

– Vicious circle: the ‘invasion’ of lower organisational levels competencies tends to be contagious throughout the chain of command; on one hand, due to the example given by upper management and on the other hand as a way to replace the ‘stolen’ responsibilities by someone else’s.

– Poor organisational alignment and focus on the business: nobody knows exactly who should do what, procedures are invalid, there is a risk of disorientation and, most probably, of general inaction.

– Responsibilities’ gap: someone taking care of others’ responsibilities may not pay due attention to their own. Some relevant decisions -blank areas on the chart- might not be made.

– Reluctance to decision-making: general inclination of professionals to avoid making decisions and being accountable for them, even those that theoretically belong to them, since they fear being corrected by a manager at any time. Some relevant decisions potentially skip.

– Breakdown of the chain of command: the capacity and autonomy of professionals is questioned, damaging their authority and creating confusion at lower levels.

– Silos creation: propensity to work in isolation, in silos, with poor collaboration between people and teams, so preventing eventual further responsibilities’ overlap.

– Wrong, hidden, uncorrected decisions: nobody is the ideal decision-maker in all areas; an individual is more likely to make a mistake when they decide on something that is not their day-to-day responsibility. Furthermore, a higher-level manager will hardly be confronted with their mistakes, which will probably be hidden and not corrected. Eventually, if the blunder is detected, it will maybe be disguised with wrong or incomplete information, diluting or diverting responsibility, which rarely will fall on the decision-maker.

– Impact on talent, motivation and performance:

• Low level of commitment through the entire organisation, due to lack of mutual trust.

• The most capable professionals, demotivated, either leave (talent is lost, maybe for the benefit of the competitors) or accommodate (talent is wasted).

• Average professionals tend to stay at their comfort zone due to the lacking accountability. If something goes wrong, any eventual reproval is not followed by negative consequences.

• The organisation loses quality decision-making skills.

• If, in addition, there is not a proper performance appraisal system, it is the perfect storm: there will not be an easy way out of the trap.

STEPPING OUT OF THE TRAP

It is not easy to detect -from the inside- if an organization has fallen into the decision-makers trap and so to start taking steps to get out of it.

Ingrained habits, a hardly visible decisions flow, the fear of professional retaliation, the avoidance of conflict or just the aim to remain at the comfort zone sometimes prevent the detection of the problem and, therefore, the search of solutions.

Besides, the solution frequently involves changing the behaviour of the highest organisational levels, with the consequent difficulty from a political and cultural point of view,

The fastest and most effective way to detect this situation and rescue the organization out of the decision-makers’ trap is to resort to the external vision of an experienced, objective, independent executive sufficiently empowered to change behaviours without long term negative consequences.

JM Noriega 2026